Action for health issues in Indigenous Australian communities

Action for health issues in Indigenous Australian communities

Why this petition matters

This Invasion Day marks 250 years since discrimination against First Nation's people began. The first fleet brought violence and disease, decimating Indigenous Australian populations. Indigenous Australians now only make up 2.4% of the Australian population. There are many factors that have lead to this and these are explained in depth bellow, but we want to focus on the solutions needed to bridge the health gap for Indigenous Australian communities:

1. Better psychosocial services

Particularly in remote Australia to combat the significantly higher rates of mental illness seen in Indigenous Australians

2. More funding and research

Specifically into diseases that impact Indigenous Australians such as HTLV-1 a disease similar to HIV which has a prevalence of up to 45% in central Australian communities.

3. Treatments for diseases

Diseases such as strongyloidiasis effect up to 60% of people in Indigenous communities. We have readily available and cost effective treatments for this disease, and yet it hasn't been administered to the communities that need it.

This Invasion Day give back to First Nation's people and help us close the health gap for Indigenous Australian Communities.

#scienceforfirstnations

As scientists we couldn't help but give you all the facts, so keep on reading for the full break down.

Health concerns in Indigenous Australian communities

Researched by Haylo Roberts, PhD Candidate La Trobe

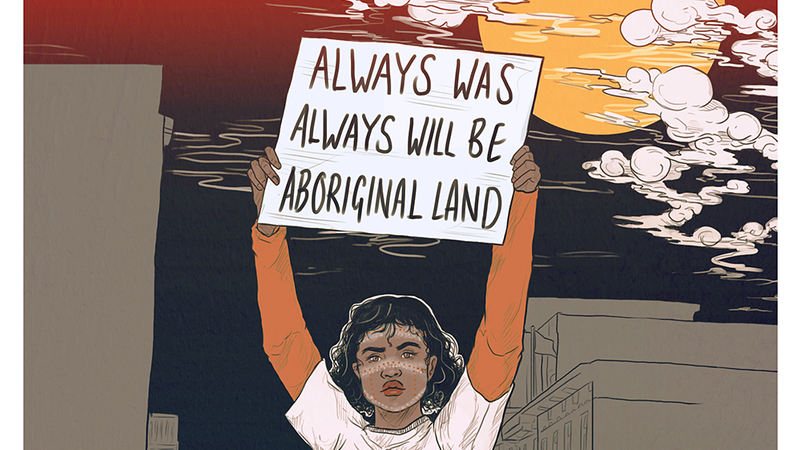

Art: Charlotte Allingham

Australia has been occupied by humans for at least 50000 years, during this time over 500 nations of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander’s peoples were established, hereby referred to as Indigenous Australians. Many of these indigenous nations had distinctive cultures, languages, and beliefs. Since the invasion and colonization of Australia by the British only 250 years ago, Indigenous Australian populations have been decimated with an estimated 90% population reduction occurring in the decade following the arrival of the first fleet [1]. The populations that were not destroyed by introduced disease or colonizer violence had either moved inland towards central Australia or already had been settled there. Today, Indigenous Australians make up just 2.4% of the Australian population – however, the burden of disease is heaviest on these Indigenous populations.

Indigenous Australians have a life expectancy at birth approximately ten years lower than nonindigenous Australians [2]. This gap is indicative of Australia’s First Peoples being left behind by health initiatives, as well as causative social, environmental and economic factors contributing to poor health outcomes [3]. The World Health Organisation outlined that social policies designed to alleviate the unequal distribution of power, income, goods and services will result in more evenly dispersed outcomes [4]. Health concerns of Indigenous Australians is a multifaceted issue, and to solve we will need impactful policies, targeted research, and data collection for monitoring efforts and reevaluation.

Education retention rates are lower for Indigenous Australians, with 55.1% of Indigenous Australian students being retained into year 12 in comparison with 82.9% non-Indigenous Australians [2]. In 2012-13 the unemployment rate for Indigenous Australians was 21%, 4.2 times that of non-Indigenous Australians, with an overall ratio of Indigenous to non-Indigenous average income of 0.7 [2]. As off the 2011 nationwide census survey, 12.9% of Indigenous Australian households are considered overcrowded in comparison to 3.4% of non-Indigenous households [2]. These inequities are identifiable determinants of health outcomes that need to be addressed as prophylactic measure.

Down the line from these social determinants we see higher rates of morbidity and mortality for several diseases. Indigenous Australian adults have a higher rate of cardiovascular disease than non-Indigenous Australians (27% and 21% respectively) and Indigenous Australians have a 50% higher risk of cardiovascular disease mortality compared to non-Indigenous Australians [5, 6]. Indigenous Australians are also 1.1 times more likely to be diagnosed with cancer than non-Indigenous Australians, with a 1.4 times higher mortality rate than non-Indigenous Australians [7]. Comorbidity is also more common in Indigenous Australians, in 2011-2013, 38% of Indigenous adults with cardiovascular disease, diabetes or chronic kidney disease had 2 or more conditions – compared with 26% of non-Indigenous adults [5]. It is worth noting that these stats are for both Indigenous Australians living both remotely and non-remotely, however, the frequency of morbidity and mortality of various diseases is higher in Indigenous Australians living remotely. There is a higher proportion of Indigenous Australians living in remote areas – 21% - compared to non-Indigenous Australians – 2% [2].

In addition to higher frequencies of common diseases in Australia, Indigenous Australians are also afflicted with high rates of neglected diseases that are relatively rare in non-Indigenous Australians. Human T-Lymphotropic Virus Type 1 (HTLV-1) is an oncogenic retrovirus which is implicated in respiratory pathologies, adult T-cell lymphoma, and myelopathy [8]. HTLV-1 is considered the most carcinogenic microorganism to infect humans known, and strikingly some Indigenous Australian communities in central Australia have prevalence of HTLV-1 seropositivity up to 45% [9, 10]. HTLV-1 is transmitted through infected bodily fluids, via breastfeeding, intercourse, sharing of needles, and transfusions / transplants [11]. HTLV-1 infection in central Australia was highly associated with bronchiectasis, for which prevalence rates in Indigenous adults in central Australia are the highest worldwide [12]. Co-endemicity of HTLV-1 and Strongyloides stercoralis, the etiological agent causing strongyloidiasis, is also of concern, as this co-infection can impede treatment efforts for strongyloidiasis and result in higher rates of complicated strongyloidiasis [13, 14]. S. stercoralis is an intestinal nematode uniquely able to complete its life cycle and proliferate within a host, termed autoinfection [14]. Autoinfection occurs continuously however in immunocompromised individuals – such as those coinfected with HTLV-1 – autoinfection is enhanced, resulting in higher larval loads disseminating and more frequent inflammatory responses [14].

Some Indigenous Australian communities have shown S. stercoralis seropositivity rates of up to 60%, well over the threshold for hyperendemicity [15]. In places where HTLV-1 and S. stercoralis are both endemic, such as central Australia, HTLV-1 infection is implicated in a higher prevalence in S. stercoralis infection [13]. In comparison to HTLV-1 there is a readily available treatment for S. stercoralis infection which can be implemented. Ivermectin is an antihelmintic drug used for treatment of several parasitic infections including scabies, onchocerciasis and lymphatic filariasis. Just one dose of ivermectin has been shown to reduce 75% of seropositivity of S. stercoralis in a community [16]. Ivermectin treatment is used worldwide for mass drug administration of neglected tropical diseases, is relatively lost cost, and could serve as a control measure for S. stercoralis in Indigenous communities while the core factors behind the striking frequency of S. stercoralis infection are addressed – namely, overcrowded housing and a lack of functioning toilets [13].

Strongyloidiasis is ultimately a disease of poverty that reflects the inequities and poor socioeconomic situation of Indigenous Australians. HTLV-1 is a neglected disease despite the vast similarities the disease has with HIV, and implementable strategies that could be adapted from long running HIV strategies. 26th of January 2020 marks 250 years since Australia was invaded. As scientists we need to ensure the implementation of policies with Indigenous Australian health at its core and it’s time we start researching and finding ways to improve quality of life for Indigenous Australians.

References

1. Konishi, S.J.A.H.J., Aboriginal History Journal: Volume 38. 38.

2. AIHW, The health and welfare of Australia's Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples 2015, A.I.o.H.a. Welfare, Editor. 2015: Canberra, Australia.

3. Donato, R. and L.J.A.H.R. Segal, Does Australia have the appropriate health reform agenda to close the gap in Indigenous health? 2013. 37(2): p. 232-238.

4. Organization, W.H., Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health. 2008: World Health Organization.

5. AIHW, Cardiovascular Disease, Diabetes and Chronic Kidney Disease–Australian Facts: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People. 2015, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare Canberra: Canberra, Melbourne

6. Diaz, A., et al., Nexus of Cancer and cardiovascular disease for Australia’s First Peoples. 2020. 6: p. 115-119.

7. Roder, D. and D.J.A.P.J.C.P. Currow, Cancer in aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people of Australia. 2009. 10(5): p. 729-733.

8. Einsiedel, L., et al., Human T-Lymphotropic Virus type 1c subtype proviral loads, chronic lung disease and survival in a prospective cohort of Indigenous Australians. 2018. 12(3): p. e0006281.

9. Einsiedel, L., et al., Human T-Lymphotropic Virus type 1 infection in an Indigenous Australian population: epidemiological insights from a hospital-based cohort study. 2016. 16(1): p. 787.

10. Tagaya, Y. and R.C.J.F.i.m. Gallo, The exceptional oncogenicity of HTLV-1. 2017. 8: p. 1425.

11. Martin, F., Y. Tagaya, and R.J.T.L. Gallo, Time to eradicate HTLV-1: an open letter to WHO. 2018. 391(10133): p. 1893-1894.

12. Einsiedel, L., et al., Bronchiectasis is associated with human T-lymphotropic virus 1 infection in an Indigenous Australian population. 2012. 54(1): p. 43-50.

13. Einsiedel, L. and L.J.I.m.j. Fernandes, Strongyloides stercoralis: a cause of morbidity and mortality for indigenous people in Central Australia. 2008. 38(9): p. 697-703.

14. Carvalho, E. and A.J.P.i. Da Fonseca Porto, Epidemiological and clinical interaction between HTLV‐1 and Strongyloides stercoralis. 2004. 26(11‐12): p. 487-497.

15. Page, W. and R.J.A.f.p. Speare, Chronic strongyloidiasis-Don't look and you won't find. 2016. 45(1/2): p. 40.

16. Kearns, T.M., et al., Strongyloides seroprevalence before and after an ivermectin mass drug administration in a remote Australian Aboriginal community. 2017. 11(5): p. e0005607.